Today on Baseball for Beginners… robot umpires made their first call in baseball yesterday and I think the way technology is being rolled out in MLB can guide improvements in the way VAR is used in football. Plus, it gives us a great excuse to talk about a fundamental part of baseball… the strike zone.

Yesterday, Thursday February 20, something new happened in baseball.

It’s an interesting development in the ongoing courtship between sport and technology and it also allows us to talk about a cornerstone of the rules that took me a while to wrap my head around when I first got into baseball. If you’re brand new to the game, you might learn something today. Hey, subscribe, will ya?

The Chicago Cubs pitcher, Cody Poteet, threw a 95mph fastball past Max Muncy of the LA Dodgers yesterday. The umpire, half-crouching behind the catcher, called it a ‘ball’. In his opinion, it had not passed through the strike zone.

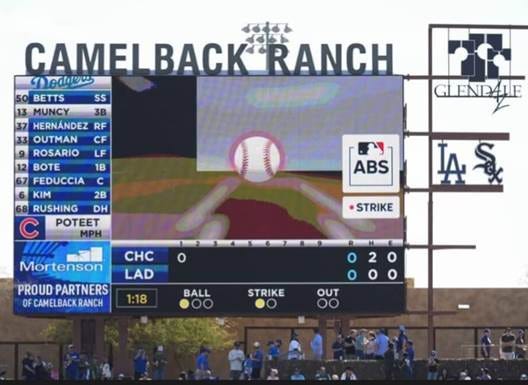

Poteet touched his cap, signalling that he wanted to challenge the call, using the Automated Balls and Strikes System (ABS). This is new technology being trialled for the first time in MLB this spring – that’s pre-season, Spring Training games only. It recreates the pitch digitally on the stadium scoreboard, showing everyone exactly where the ball was when it crossed home plate. Here’s what the crowd saw.

As you can see, the ball touches the white strike zone, and the call was overturned. This was the first successful challenge using ABS in the Major Leagues (even if it’s only Spring Training).

OK, first things first. What is the strike zone?

So, we’re talking about an imaginary area directly above home plate on the horizontal plane, and vertically from the bottom of the batters knees to a midpoint between his belt and his shoulders. Got it?

Now, look at where the umpire stands.

And remember:

these balls are passing over that tiny home plate either at speeds of around or 100mph or slightly slower but with insane amounts of spin that take them on wild parabolas.

the umpire is wearing a mask, because fastballs travel at 100mph and of course he is.

My point is, this is a very difficult decision to make. It staggers me that human umpires get it right more than 90% of the time.

And anyway, what’s the point?

Balls and strikes

If the ball touches the strike zone, it is ruled a strike.

If it does not, and the batter does not swing, it’s a ball.

And both of these outcomes contribute to the count.

Let’s look at the scoreboard from the Cubs-Dodgers game again.

The more observant of you will notice that I have artfully highlighted the record of balls and strikes during this at-bat.

At the point when Poteet touches his cap, the umpire has ruled his pitch a ball, and a previous pitch has passed over the strike zone and been ruled a strike. So the scoreboard reads one ball, one strike. 1-1. One-and-one. Balls first, pals. Always balls first.

Three strikes and you’re out. Everyone knows that.

On the other hand, four balls and you walk. That one hasn’t passed into common, Trans-Atlantic parlance. It’s simply not as catchy. But a walk is a valuable commodity – a free pass for the batter to first base. That’s the prize for having the patience and, let’s face it, the cojones, to watch the pitcher miss his mark four times before that third strike makes you look like a fool.

But what if the batter swings?

Well, if he misses the ball, it’s a strike, no matter where the ball was when it crossed home plate. And if he makes contact…

Here’s the baseball diamond, the field of play.

From the bottom, C is catcher, P is pitcher; SS is short stop; the first baseman, second baseman and third baseman complete the infield; in the outfield we have left fielder, centre fielder and right fielder.

But for today’s purposes, consider the straight lines stretching out from home plate on either side: the left field line and the right field line.

If the ball goes wide of these lines before it touches the ground, it’s a foul ball. If it is hit on the ground, but crosses the foul line before reaching either first or third base, it’s a foul ball. And if the batter tips the ball backwards and it never makes it into the field of play, that’s a foul ball, too.

And a foul ball counts as a strike.

Unless the batter is already on two strikes. Strike three can never be a foul ball. In that situation, this is a neutral outcome and the count remains the same.

And if he makes contact and the ball goes into play, that’s either going to be:

a hit – the batter makes contact and reaches base safely

a ground out – the batter hits the ball along the ground, but the fielding team throw to first base before the batter reaches there

a fly out – the ball is caught before it touches the ground

Back to Mr. Poteet. His fastball, as you will recall, was a strike, after all. So the count on the scoreboard (one-and-one) became a count of zero balls and two strikes, 0-2, or oh-and-two. Three pitches later, Max Muncy watched strike three go by and he returned to the dugout holding nothing but his bat and a piece of baseball history.

“When that ball crossed, I thought it was a strike right away,” said Muncy. “I look out there and he’s tapping his head and I went, ‘Well, I’m going to be the first one’.”

Postscript – ABS, meet VAR

As in the use of Hawkeye technology in cricket and tennis, ABS is used on a limited appeals basis.

Only three people can appeal the umpire’s call: the catcher, the pitcher and the batter. And each team can only have two unsuccessful appeals.

Not only does that structure limit delays, it also bakes in the clear-and-obvious-error benchmark that VAR rode into town on.

If one or two designated players had to make instant decisions on whether or not to appeal a decision in football, the officials would revert to making their best calls in real time (no delayed flags), and the majority of challenges would only be used when the players on the field were reasonably sure an error had been made.

VAR can be better deployed in elite football. Maybe – maybe – the latest team sport to adopt a new form of technology can help football get to the best version of assisted refereeing.

Hey, thanks for reading. Stick around for the season, it doesn’t cost anything. And if you’re enjoying baseball for beginners, I’d appreciate it if you shared it. Peace out.